St George From the Roverella Altarpiece San Diego Museum of Art

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece (or Adoration of the Shepherds with angels and Saint Thomas, Saint Anthony, Saint Margaret, Mary Magdalen and the Portinari family), 1477-78, oil on forest, 274 x 652 cm (Uffizi, Florence). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, c. 1476, oil on forest, 274 x 652 cm when open (Uffizi) (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC Past-NC-SA 4.0)

Artworks are powerful things. Hugo van der Goes'due south Portinari Altarpiece acquired quite a stir when information technology arrived in Florence—the city that was to become its permanent home. Van der Goes, master of light and minute descriptive details, is considered one of the greatest Netherlandish painters of the second half of the fifteenth century. The Portinari Altarpiece is a large triptych that was deputed by an Italian named Tommaso Portinari, who was living in the Netherlands.

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, c. 1476, oil on wood, 274 x 652 cm when open (Uffizi)

An Italian family in the Due north

Just as today, people in the renaissance often traveled extensively or fifty-fifty moved permanently for work. Portinari, his wife Maria Maddalena Baroncelli, and their children were living in Bruges at the fourth dimension of this painting'due south creation. Tommaso worked as a high-ranking agent of the Medici banking industry, helping to run a branch of the bank in Bruges. The Medici were i of the most powerful families in western Europe, and their lineage had developed an extremely wealthy cyberbanking, mercantile, and political family unit. Agents throughout Europe managed branches of their cyberbanking empire.

The Portinari family and Florence'south Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova

Façade of the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova (photograph: Mongolo1984, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Interior of the church building of Sant'Egidio (photo: Mongolo1984, CC BY-SA iv.0)

While Tommaso had made a proper noun for himself in Bruges, his family remained important to the history of Florence. In 1288, Tommaso's ancestor, Folco Portinari, founded the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, today the oldest performance hospital in Florence. In the 1420s, the Portinari family supported farther renovations to the hospital, which, by the fifteenth century had around 200 beds (upwards from 12). As with many hospitals today, Santa Maria Nuova had a continued church, Sant'Egidio.

The Portinari Altarpiece was commissioned for the main chantry of this church, and was simultaneously a mode for Tommaso to perpetuate his family's name and importance in conjunction with the city of Florence and the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova.

The Portinari Altarpiece stands as a highlight of Tommaso's career and the public prototype he hoped for his family name to retain. Unfortunately, the Portinari family vicious on difficult fiscal times not long after this painting'south creation, as Tommaso lost the Medici family a keen deal of money through loans to Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy, which were never paid dorsum in full.

Hugo van der Goes and due north-s exchange

Portinari's choice of a Netherlandish artist to complete this great altarpiece to be sent dorsum to Florence helped to finer alter aspects of Italian art. The latter one-half of the fifteenth century was characterized past increased artistic substitution between northern European and Italian artists. Italian artists were enthralled past Northern artists' careful attention to individual details and still-life minutiae incorporated in architectural settings and landscapes. Hugo van der Goes was considered a chief of such careful, minute details and his talent was oftentimes compared to that of Jan van Eyck, considered one of the greatest painters of the early fifteenth century. Look closely, for example, at van der Goes'southward rendering of the foreground angels' garments. It appears as though we can physically bear upon the gold brocade of the textile. And the clear vessel in the foreground likewise flawlessly seems to capture, reflect, and refract light.

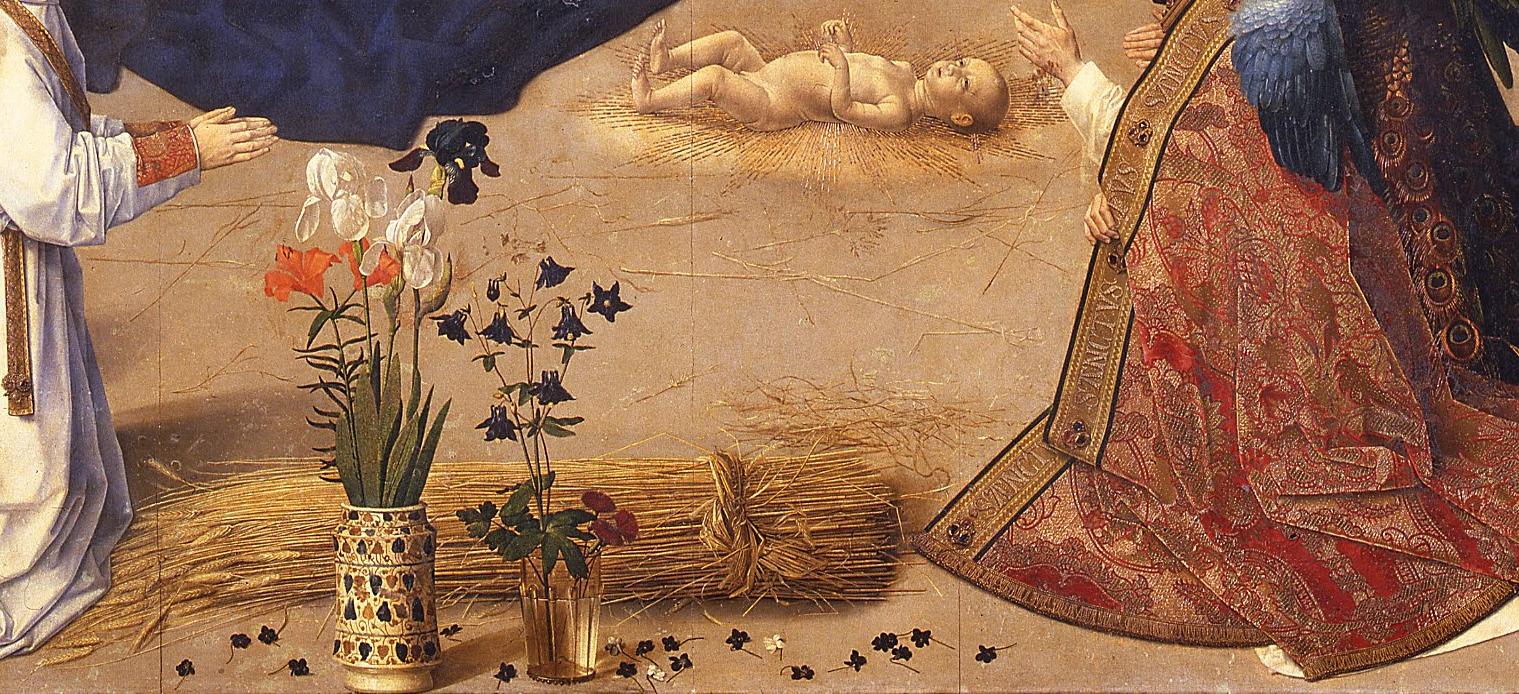

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, detail of the centre panel foreground, c. 1476, oil on woods, 274 10 652 cm when open up (Uffizi)

Such tiny details are found throughout the Portinari Altarpiece, and nearly all of them hold some iconographic significant. When this painting finally arrived in Florence in 1483 for its installation in the church of Sant'Egidio, it had a direct, visible effect on artistic production in Italy. A particularly famous painting that clearly recalls the Portinari Altarpiece is Domenico Ghirlandaio's Adoration of the Shepherds, painted in 1485—only 2 years after the Portinari Altarpiece arrived in Florence. In Ghirlandaio's painting, i can see that the shepherds adoring the Christ child are rendered with such individualized particular that they feel like portraits, equally in the Portinari Altarpiece. The grouping also takes the exact same formation as the three shepherds pictured in van der Goes's work.

Left: Domenico Ghirlandaio, Birth and Adoration of the Shepherds, 1485, tempera and oil on console, 167 10 167 cm (Sassetti Chapel, Santa Trinità, Florence); right, Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, center console, c. 1476, oil on wood, 274 ten 652 cm when open (Uffizi)

Layered iconography

Iconography, commonly used in the field of art history, is the written report of the symbolic meaning of things found in works of art. In northern renaissance fine art, artists often used sure figures, objects, and even depictions of biblical or historical events to symbolize something more to catamenia viewers than what was seen on the surface. The iconography throughout the Portinari Altarpiece is extensive and quite complex.

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, closed, c. 1476, oil on forest, 274 x 652 cm when open (Uffizi)

Triptych altarpieces like the Portinari Altarpiece would have been kept airtight, except on holidays and special feast days. Therefore, the exterior of the folding side wings of such artworks were typically painted. The Portinari Altarpiece'due south outside is decorated with a depiction of the Annunciation, the biblical event when the Angel Gabriel appeared to the Virgin Mary to tell her that she had been chosen to carry the son of God. This moment is understood in the Christian faith every bit the beginning of flesh's salvation. Here, we see it essentially frozen in fourth dimension, as the creative person has chosen to paint these figures in grisaille . These fake sculptural figures are located in shallow architectural niches and reveal van der Goes'southward incredible creative talent in their conceivable naturalism.

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, c. 1476, oil on wood, 274 x 652 cm when open (Uffizi)

Upon seeing the Portinari Altarpiece opened, i can imagine that whatever menstruum viewer would have been stunned past the elaborate details and bright colors contained on the three panels inside. In the center console, nosotros are privy to the quiet, magical moment just afterwards Christ's birth, the Nativity. Angels surround the kneeling Virgin Mary and newborn Christ child, and the three shepherds have rushed in from the countryside to bear witness to the miracle. This scene would have been instantly recognizable to whatsoever period viewer, and almost would take noticed the iconographic details—certain objects and scenes that held multiple meanings.

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, item of shepherds, c. 1476, oil on wood, 274 ten 652 cm when open up (Uffizi)

Far in the distance, behind the heads of the shepherds, we run into those very same shepherds attention to their flock on the hillside. These tiny figures make gestures of surprise as an angel appears to a higher place them. This is the moment of the Annunciation of the Shepherds, when they were told that Christ had been born. In the repetition of these shepherds in the background and once more in the foreground, the creative person has used what is called continuous narrative, wherein figures are repeated inside the same frame of an artwork to evidence more one moment of a story.

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, eye panel, c. 1476, oil on wood, 274 x 652 cm when open up (Uffizi)

Moving to the left side of the central panel, nosotros see Joseph, Mary'south husband, clothed in a rich red mantle. His hands are together in a gesture of prayer or supplication, as he honors the newly built-in Christ child. Just in front of him is a clog that has been removed. This detail symbolizes that this scene is taking identify on holy ground. In a higher place Joseph are two angels. Note that many angels in this piece of work are dressed in elaborate liturgical, priestly garments (such as the one immediately in a higher place Joseph's head and those on the right side of the image). This would have reminded viewers of the important sacrament that took place at the altar, in front of this altarpiece—the sacrament of communion (where the bread and wine miraculously transform into the trunk and blood of Christ). One affections, however, who hovers just above the ox and the ass (and is barely visible), has a somewhat nighttime, foreboding countenance. This is believed past some art historians to stand for the lingering threat of Friction match (Satan).

Everything centers around the Nascency

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, detail of center panel, c. 1476, oil on woods, 274 ten 652 cm when open up (Uffizi)

In the center are the most important figures in the scene, the Virgin Mary and the infant Christ. It may seem strange that Christ is laying naked on the blank, hard footing, and that rays of calorie-free announced to emit directly from his body. Nevertheless, this imagery is drawn from the writings of a medieval visionary named St. Bridget of Sweden. Past the fifteenth century St. Bridget'due south vision of the Nativity had get the inspiration for many depictions of this moment. Mary kneels beside Christ on the ground, a position meant to emphasize her humility, and bends over in somber adoration of her child. And her solemn nature, in this case, is meant to foretell what is to come—that she volition have to cede her son for the salvation of humanity.

Perhaps the almost striking detail in the central panel is the group of objects in the foreground. Imagine this altarpiece in its original location, just above the chantry of Sant'Egidio. The ii vases would announced nigh as though they were sitting on the altar itself. Detect, too, that the sheaf of wheat behind them is quite similar in color to and situated directly parallel with Christ's body. At Mass, a priest would consecrate the Eucharist—the bread and vino—thereby turning it into the body and claret of Christ (according to Catholic tradition), which would be consumed in remembrance of his sacrifice. The hem of the crimson and gold brocaded vestment worn by the affections foregrounded on the right is embroidered with the repeated word "sanctus," or holy, referencing the moment of the consecration of the Eucharist. The positioning of Christ'south body parallel to the sheaf of wheat, which in plow would exist parallel to the physical bread on the altar, functioned as a stark reminder of what really took identify at communion. The image masterfully creates a visual equation between the bread, the wheat, and Christ's body.

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, particular of center panel foreground, c. 1476, oil on wood, 274 x 652 cm when open up (Uffizi)

The vases and flowers merely in front of the wheat are carefully studied depictions of recognizable flowers that each held symbolic meaning for period viewers. The Castilian albarello vase on the left is a type of vessel that traditionally held herbs and ointments used by apothecaries, an artistic pick which was about certainly meant to comment on the altarpiece'southward location in a infirmary's church. The albarello vase holds ii white and one majestic iris, along with a crimson lily. These flowers represent the purity (white), royalty (majestic), and Passion, or tortures, (red) of Christ. This vessel is besides decorated with an ivy leaf motif that resembles a grape vine, alluding to wine, and therefore, to the blood of Christ, consumed with His trunk during Mass. The presence of this vase also reminds us that Valencia (in Spain), Italia, and northern Europe were engaged in extensive trade during this time, and expanding their trade across the world. Spanish lusterware, similar this vase, was a popular luxury merchandise item in the fifteenth century, admired for its cogitating surface. The luster technique derives from Islamic pottery, and information technology is important to continue in mind that the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) had a large Muslim population.

The clear vessel to the right holds three cherry-red carnations and seven blueish columbines. The 7 columbines are symbolic of the 7 Sorrows of Mary, while the three ruddy carnations make reference to the iii bloodied nails at Christ'southward Crucifixion. As y'all tin see, many of these flowers were meant to remind viewers of what was to come up for Christ.

The story grows, and so does the Portinari family

Having discussed the details of the central panel, let's take a look at the ii side panels. In the backgrounds of each of the side panels, we find scenes that occurred before, subsequently, and during the principal scene of the Nascence in the middle. And simply as the story is expanded in the side panels, we come across that Tommaso and Maria have expanded their lineage, as well. Van der Goes, a master of detailed portraiture, depicted Tommaso Portinari in the left panel, kneeling in prayer as he faces the miraculous scene in the center. Because he paid for this elaborate souvenir, his family unit'due south inclusion in the altarpiece essentially guarantees that they volition forever exist included in the daily prayers carried out in the church. Tommaso is accompanied by their 2 sons (as of the creation of this painting c. 1476), Antonio and Pigello, who kneel behind him. Notation that, even if Tommaso were continuing, he would still be noticeably smaller than the ii figures who stand backside him. This is known as hierarchy of calibration, where a visible divergence in size between figures indicates that larger figures are of higher status. In this instance, the larger figures are saints. St. Thomas, the name saint of Tommaso, works as his intercessor, finer "introducing" him to the scene in the centre and helping to convey his prayers to heaven. Backside St. Thomas is St. Anthony, the name saint of Antonio, besides as a "plague saint" who was frequently invoked by the ill, suffering, and dying. His presence makes yet another connectedness to the altarpiece's original infirmary location.

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, side panels, c. 1476, oil on wood, 274 x 652 cm when open (Uffizi)

In the right panel, Maria Maddalena Baroncelli kneels in a position that mirrors her husband'due south, accompanied past their daughter Margarita. These ii figures are joined by their name saints, Mary Magdalene and St. Margaret. Interestingly, nonetheless, it is St. Margaret who stands behind Maria, not her name saint Mary Magdalene. St. Margaret is the patron saint of childbirth, and is evoked past pregnant women and those in labor in hopes of a successful process and outcome. St. Margaret is typically depicted every bit emerging from the mouth of or standing atop a dragon, as seen here (her fable explains that she survived existence consumed by Satan, disguised every bit a dragon, whose stomach then rejected her and she emerged unharmed). Equally such, information technology is speculated that this may have been a deliberate choice, equally Maria'southward master role every bit a wife in the fifteenth century was to bear children and continue the Portinari lineage, so she felt a stronger connection to St. Margaret at this point in her life.

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, details of the Holy Family unit and the Magi, c. 1476, oil on woods, 274 x 652 cm when open up (Uffizi)

Merely every bit in the primal panel, the side panels also include small scenes in the groundwork. In fact, the left panel continues the theme of childbirth already indicated past the Nascence in the center and the presence of St. Margaret in the right panel. Far in the distance behind St. Anthony'southward head, we see Joseph attending to a significant Virgin Mary who has decided to walk rather than ride her donkey. This is a forerunner to the miraculous nascence that volition soon occur, the Nativity. In the right panel, the landscape is populated by scenes of the three kings, the Magi, on their journeying from far parts of the world to visit the newborn Christ.

What the northern painters did best

Hugo van der Goes'south Portinari Altarpiece encompasses the numerous aspects of northern renaissance painting that enthralled those in other parts of the world. This detail artwork perfectly embodies all the things that northern European painters were thought to do best—the rendering of complex landscapes that stretch far into the distance, skies that seem to capture light at different times of the day or under different circumstances, faces that announced highly individualized, fifty-fifty when they are non intended to be recognizable portraits, and carefully rendered, incredibly minute details throughout. Considering this triumph of creative virtuosity, along with the work's fascinating layers of symbolism, the direct and immediate affect of the Portinari Altarpiece on the art earth of belatedly-fifteenth-century Florence comes equally no surprise. It is after this moment that we see, in particular, increased individualism in Italian faces and, perhaps even more than importantly, a swift rise in the utilize of oil pigment in Italian city-states.

Additional resources:

Online bout of this painting (from the Uffizi)

Read about this painting on the Uffizi website

Learn more nigh the expanding the renaissance initiative

Victor Coonin, "Altered Identities in the Portinari Altarpiece," Source: Notes in the History of Art 36, no. 1 (2016), pp. four–15.

Roger J. Crum, "Facing the Closed Doors to Reception? Speculations on Foreign Exchange, Liturgical Variety, and the 'Failure' of the Portinari Altarpiece," Fine art Periodical 57, no. 1 (1998), pp. v–13.

Margaret 50. Koster, Hugo van der Goes and the Procedures of Art and Conservancy (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, Harvey Miller Publishers, 2008).

Julia Miller, "Miraculous Childbirth and the Portinari Altarpiece," The Fine art Bulletin 77, no. 2 (1995), pp. 249–261.

Paula Nuttall, From Flemish region to Florence: The Impact of Netherlandish Painting, 1400–1500 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004).

Robert M. Walker, "The Demon of the Portinari Altarpiece," The Art Bulletin 42, no. iii (1960), pp. 218–219.

Source: https://smarthistory.org/van-der-goes-portinari/

0 Response to "St George From the Roverella Altarpiece San Diego Museum of Art"

Post a Comment